In fact, I often get a blank look when I talk about tweaking our normal strategies, goals, and metrics to emphasize learning via structured experimentation or what I like to call honest experiments. I suspect it feels unnatural to focus on learning, as if that somehow diminishes the hard work, experience, and intellect that informed choosing a strategy, key objectives, and other measures and metrics. Maybe it’s our brain’s love of the status quo, or any number of our cognitive biases, or the social threat involved with possibly being shown to be be wrong especially when the stakes are high. Maybe it’s a fear of slowing things down or simply not knowing how to do it with existing tools and processes.

Truly wise leaders have learned to be intellectual humble while also having an opinion or thesis. The more they learn about the world, the more they realize how little they know. They’ve been wrong before and recognize that it’s very possible they’ll be wrong again so they hold their current ideas lightly. Their focus is on learning and achieving desired results with others. It is emotionally liberating and intellectually satisfying to redirect one’s emotional energy from looking smart into actually becoming smarter with your colleagues in service of something meaningful. “Figuring it out together” is often one of the most satisfying memories you’ll have in your career, so in my opinion anything we can do to foster the polarity of achieving AND learning is a business imperative. When you compliment these experiments with deliberate development practices described in “An Everyone Culture” (basically people share their leadership, technical skills, or even experiences with each other and then take on key deliverables specifically so they can stretch themselves while helping achieve results that matter) it further accelerates professional growth which in turn enhances psychological safety, commitment, retention, and often smart risk taking all of which are competitive differentiators.

It’s a business imperative because it today’s world individuals, teams, functions, cross-functional partnerships, and organizations all need to proactively develop something called adaptive capacity. In the book “Adaptive Capacity: How Organizations Can Thrive in a Changing World” Juan Carlos Eichholz differentiates a technical challenge from an adaptive challenge, and the problems that are created when leaders misdiagnose one from the other. Technical problems can be incredibly hard problems to solve, but with enough expertise and resources most people can leverage existing information and resources to make sufficient progress and/or solve their problems. When you face an adaptive challenge, a disequilibrium arises often in the form of a problem and you (and your team and organization if this is a large enough problem) must engage in a reframing process and reassessment of “mentalities and behaviours, which in turn were connected to assumptions, values, loyalties, attitudes, competencies, and habits that needed to be questioned. This is the process we call adaptive change.” There are tons of books written on adaptive leadership and I will write more about this topic, but suffice it to say developing adaptive capacity takes a long, long time for individuals and intentionally developing adaptive capacity at all layers of an organization is an ongoing, very difficult task above and beyond executing on your short term plans. The reason I emphasize honest experiments (strategies, org design, you name it) is to develop adaptive capacity across every person and layer of the organization. Adults learn by doing and reflecting and this is a pragmatic, results-focused way to get stuff done, improve more quickly and profitably via data, and to grow your consciousness and capabilities at the same time. When this becomes integrated into the normal way a team of people work together it shapes the culture.

Don’t over think this; keeping it simple enough is key. The following steps and tools come from a white paper published by Twilio Segment and Growth Masters (thank you!)

1. Identify a gap or opportunity: Asking your team or customers (or observing customer behaviour or key metrics) to identify friction points with your service or product can help you identify possible improvements to execution and/or potentially new ways of providing the service or product (lower cost, niche offering, more features, less bureaucracy, more profitable offerings, etc.). A wise coach once told me that people tend to want aspirin for their headaches or vitamins to help them develop new capacities or achieve something meaningful, so even being playful with your team and asking them to identify potential places to have less headaches and/or become a more capable team or organization can be sufficient to stimulate ideas which you can then group and explore in more depth.

2. Decide how to solve the problem: “The next step is to brainstorm ways to solve the issue. This is where your gut instinct comes into play. While you wouldn’t want to make a critical decision on gut alone, you can and should take inspiration from what your gut tells you. After all, you’re about to put it to the test! Try to come up with as many ideas as possible before choosing the one you want to move forward with.”

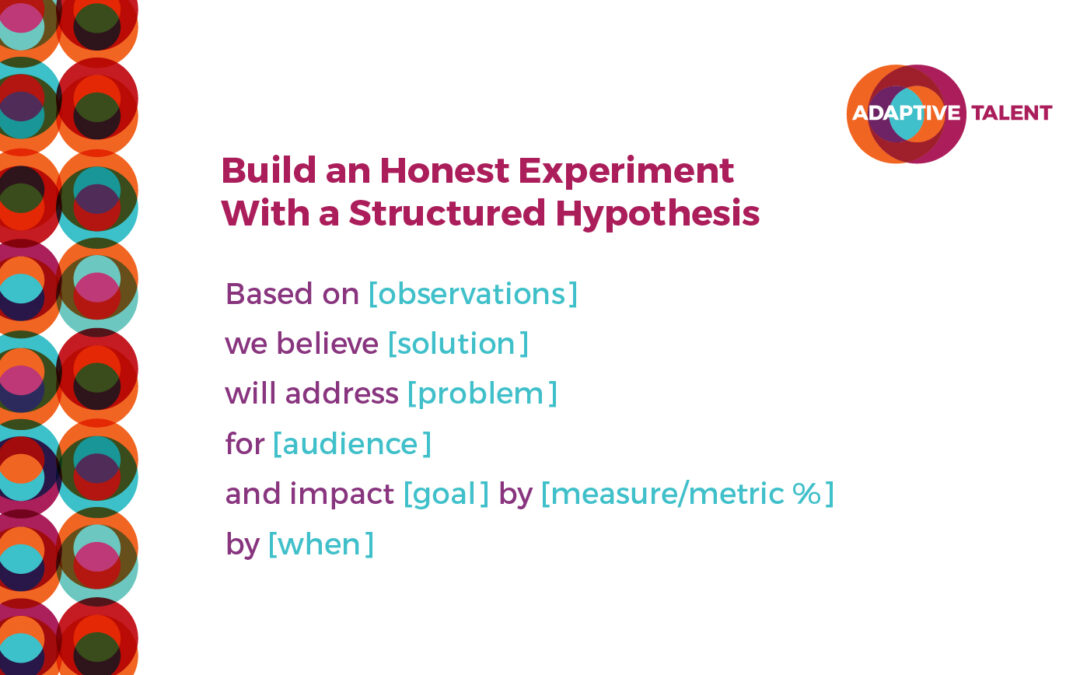

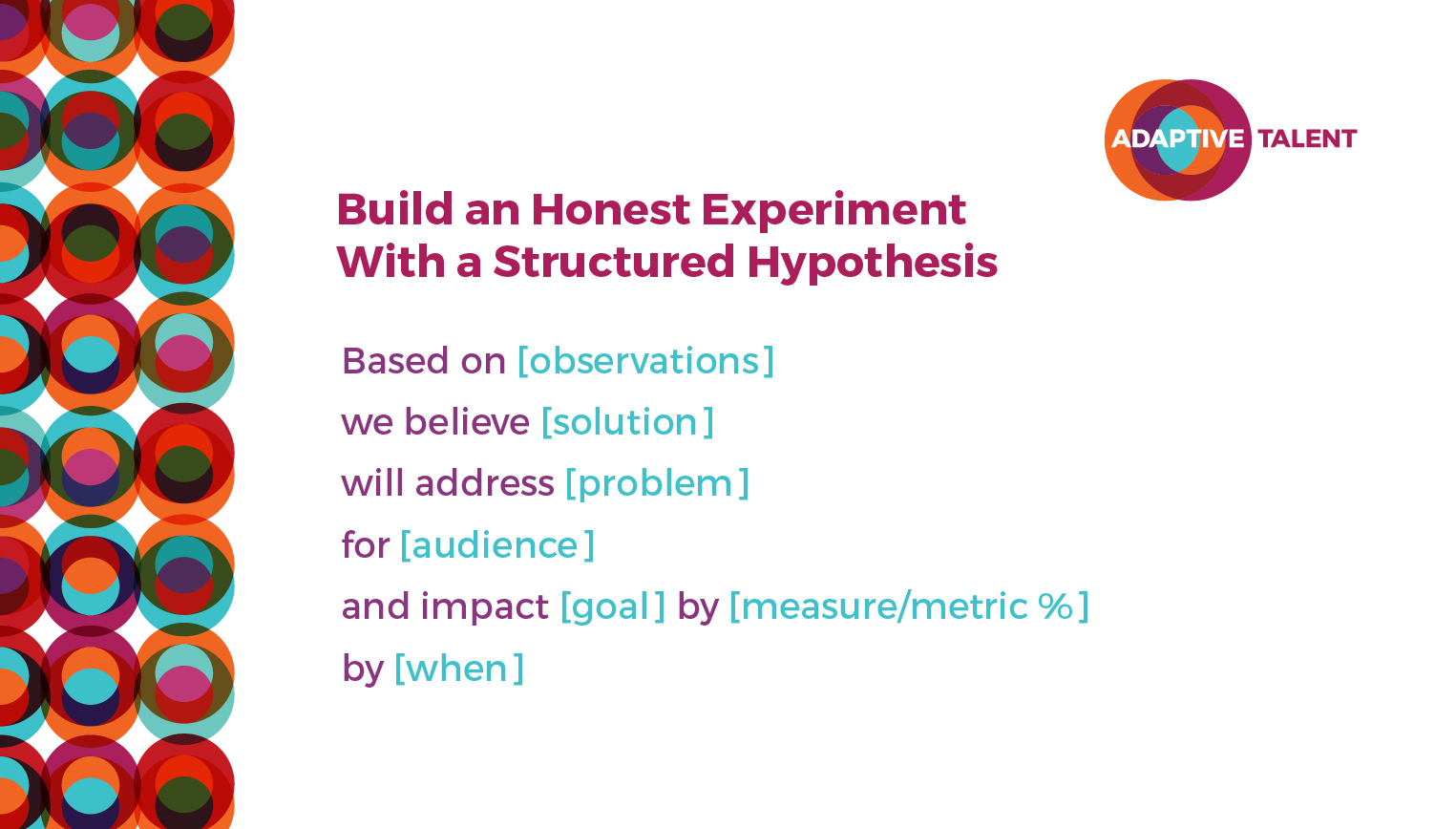

3. State your hypothesis: “A hypothesis is a prediction based on limited evidence that must be tested to determine whether it’s true. It invites you to document the problem, propose a solution, and anticipate results in just a few sentences. In this step, you’ll craft a precise hypothesis that can be proven wrong. For a simple yet effective hypothesis, use this framework: Based on [observations], I believe [solution] will address [problem] for [audience] and impact [metric] by [uplift].” There’s something called retrospective coherence which is the tendency by people to rewrite history or their opinion on a topic after the fact, and people often don’t know they’re doing it. So if you think the red ball will roll faster because of the new grease and instead it turns out that it slows it down, you might find yourself saying “that was always a long shot” of an idea. When we write things down we’re focused on learning as a group better and faster, and it’s an explicit acknowledgement that being a human being comes with all sorts of biases that we just need to work with.

4. Prioritize your experiments: Let your team decide which experiments they want to run first, and help them explicitly map out why as a way of practicing strategic thinking, story telling, and deepening their understanding of this area of your business. The more the team runs honest experiments across its key activities the more they will see the interdependencies across them and the more capable they will be to lead change at greater degrees of scale. It’s one thing to just follow a process but an entirely different level of abstraction to think about how to improve things and not screw something else up in the process. This is a great “cheap and cheerful” way to develop your people and your business at the same time, and it appeals to one’s desire for agency which is a huge motivator for most people.

You might notice that some people just don’t love someone running experiments on their idea/process/whatever. They may associate their “thing” with their identity a bit too closely or may not be quite comfortable with a growth mindset where progress is more valued then perfection, so my advice is to make sure people understand these concepts and help them reflect on their own feelings that arise with experimentation, especially if they or others are experimenting on something they created or feel pride about. As I mentioned above, when you combine this kind of work with learning out loud, like deliberate development, it creates even more psychological trust and normalizes the expected mistakes that come from growing and experimenting.

5. Create your test plan: “Once you’ve identified which experiment you want to run, it’s time to create your test Introduction plan. This document should include the purpose of your test, a copy of your hypothesis, details about the different variants you plan to test, specifics about how and what you will measure, the location where your test will take place, details about your audience and sample size, and your planned test duration.” The white paper is focused on website and other marketing metrics, so if you’re doing this on a “normal” business process (for example, inventory counts in a warehouse) you can get creative with whatever qualitative or qualitative measures make sense to you and those who rely on your role, service, or product.

6. Validate your idea: “Before launching an experiment, savvy growth leaders first validate their hypotheses. To do so, they typically turn to user research. By putting your variants in front of a handful of real users, you reduce the risk of burning your entire sample with a broken experience. This protects your brand from unnecessary harm.” If you’re doing this work internal to your team you can usually find a manager or Director who is an early adopter or has a lot of opinions on your internal service model, so often they can help you review your test plan and logic and enhance it. The best part of all of this is you do not need to be flawless or all knowing; just focus on being intellectually humble, collaborative, and committed to getting better.

Make sure people know you’re going to be tinkering with the status quo in service of improving things and be prepared for hiccups. Just make sure there’s some sort of notice and coordination to experiments being run so that people aren’t having to navigate eight new things at once.

7. Launch your test: “Once you’ve validated your hypothesis, it’s time to release your experiment out into the wild. The faster you do so, the faster you will learn—and the faster you learn, the faster you’ll maximize your impact. Your test duration will depend on your target sample size and monthly traffic, but experts agree it should last at least one full business cycle.”

8. Evaluate the results: “Once your test has run its course, it’s time to crunch the numbers. Do they reach statistical significance? Are the results in favor of or against the change? What have you learned? You may also notice unintended consequences, so it’s important to develop a clear picture of what actually happened. For example, you may notice an increase in paid signups instead of free trials. While that may not have been your prediction or goal, it still provides you with important lessons.”

DecisionWise had a good tip here: “A source of creative inspiration comes from what the United States military calls After Action Reviews (AARs). In the mid-1970s, the U.S. Army made AARs standard operating procedure. They were adopted in order to capture lessons from their various training exercises, and a crucial goal was to make reflection and learning routine.

The military’s AAR process can be formal or informal, but four key questions should be addressed:

– What did we (or I) set out to do?

– What actually happened?

– Why did it happen?

– What are we going to do next time?

In addressing these questions, 25% of the time should be allocated to questions one and two, with another 25% going to the third question. The last question should be given at least 50% of the time.”

My last piece of advice on all company processes is to have some sort of check-in built into all team playbooks or regular activities like goal setting, time allocation analyses, budgets, you name it. Just like you need to weed your garden regularly, you need to weed your team of old school, manual, or outdated ways of working. This stuff doesn’t happen magically, so you might keep a record of your top 10-20 processes, experiments, participants and those accountable for them, and a check-in date by which the team turns its attention to seeing if how they’re working is producing the desired effect. When people know you’re helping them get rid of “stupid” steps or friction points in service of them doing more interesting work or activities that your customers value more it makes these check-ins much more intriguing.

---

Adaptive Talent is a talent consultancy designed to help organizations achieve amazing results and ongoing adaptability. Founded in 2008 and based in Vancouver, Canada we offer retained and contingent search, assessments, training, leadership coaching (1:1 and group), leadership development programs, and culture & organizational development consulting.